Disastrously unprepared and chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan is surely going to go down in the history books as one of the biggest self-inflicted humiliations of the American superpower. But for all the ridicule it has drawn, it’s a far bigger issue for Russia and China (among other regional stakeholders) than the US.

Many have drawn comparisons between the events in Kabul and the fleeing of Saigon in 1975. And as unbelievable as the images from the Afghan capital are, the parallel is not unwarranted for another reason: that the failure to repel the communists in Vietnam turned out to be quite inconsequential to America and quite devastating to the Vietnamese, who continue to suffer poverty half a century later.

In this sense, Taliban’s victory presents a comparable pain for the Afghans, now under the boot of religious extremists about to take them a few centuries back in time.

But for the US, aside from being a source of international mockery (particularly days after president Biden assured the press that Afghan forces are well-trained and equipped), it is unlikely to present a mortal threat - or any significant threat at all.

Thankless Duty

“War is the continuation of politics by other means,” Clausewitz observed. And if we strip away the media narrative of subsequent American administrations, which had to sell their voters on a costly intervention thousands of miles from home by promising to leave behind a stable, peaceful country, this is what the “war” in Afghanistan was - another means of conducting much necessary, if thankless, political duties.

Given the circumstances surrounding 9/11, Taliban rejection to give up Osama bin Laden and the possibility of future attacks, sending troops in was the only rational decision - and one which bore fruit.

It brought the violence to terrorists, away from American and European civilians. In the process, Al Qaeda was crushed, Osama bin Laden killed and the threats in the West have been reduced to random lone-wolf attacks using rented cars or kitchen knives (nothing even remotely as spectacular as flying jet airliners into skyscrapers).

Understanding these accomplishments, can we say that American intervention in Afghanistan was a mistake? Not really. Were thousands of lives and billions of dollars completely wasted? Surely not. Is the world going to see a revival of organized terror groups capable of carrying out another 9/11? Probably not either.

2021 is not 2001 – the world is a different place and none of the participants in the conflict are quite the same either.

Mass media of the world continue framing Afghanistan as an American issue but in reality the US is not even in the front row of countries directly affected by the situation there.

Since there was never any discernible intent to leverage American presence in Central Asia for greater geopolitical goals, the mission’s objectives were completed in part with crippling Al Qaeda and killing Bin Laden, and in part due to evolution of extremism itself.

From analog to digital terrorism

Back in 2001 the internet was still a novelty, Facebook and Twitter didn’t exist and Google was just 3 years old. Extremism was still in its “analog” period, when jihadists hardened by years of wars they somehow managed to survive, formed organizations that trained fighters to plan and commit highly deadly terror attacks abroad.

But as years went by, Al Qaeda’s exposed camps were easy targets for American bombardments, which could wipe jihadist units out and push their remnants into hiding.

The Internet helped Al Qaeda or ISIS adopt the modern remote work-from-home lifestyle long before Covid-19 as it has allowed them to act in a far more opaque, distributed way just until a particular attack is about to be carried out.

It turned out that even the highly organized, wealthy and well-equipped Islamic State found it easier to conduct attacks in the West by using the web to radicalize individuals and organize smaller terror cells, which would go after soft - random pedestrians, journalists or concert spectators - rather than high profile targets.

With the rise of the internet, social media and smartphones, terrorism in the West has entered its “digital” era, with extremists hiding behind online encryption, inspiring, recruiting and training new fighters all over the world using easily accessible consumer technology.

Their ability to inflict damage in the developed world is no longer contingent on having a strong, organized presence on the ground in any one location. They don’t need Afghanistan like they used to - at least not for launching their attacks in developed countries.

And Taliban itself may not be willing to give them much space, given the past conflicts and the American retribution their presence brought 20 years ago.

In fact, Talibs have reportedly already executed a former ISIS commander, held in a prison in Kabul that they broke open. Zia ul-Haq (aka Abu Omar Khorasani), the former head of Islamic State in Khorasan, was shot dead without needless trials - likely a form of retribution (and precaution) given the violent conflict ISIS started with the Taliban in 2015, trying to splinter the Afghan group. Ultimately, it was settled by American bombs beating ISIS back by 2019.

Ambivalence abound

Afghanistan returns to being a regional rather than global problem. Taliban takeover is a direct threat, first and foremost, to Pakistan, that has for years funded the group, parts of which eventually turned on it and erupted as the local branch using the porous western border to launch attacks over the past 14 years.

This is a problem for the 220 million strong, highly diverse and conservative Islamic society with many jihadist sympathizers who may now be emboldened by Taliban’s success.

Ironically, Islamabad has officially cheered their victory, as they have ousted a far more Indian-friendly government of Ashraf Ghani. That said, Pakistan remains geopolitically torn between its eternal conflict with India and the extremism spilling over across its western border, threatening to splinter its society.

On the whole, open war with India is a remote (however drummed up) threat, considering that both countries are nuclear powers. Violent jihadist insurgency, however, is not only a threat but has been a reality for many years now (with extremists occasionally seizing parts of the border territories from Pakistan).

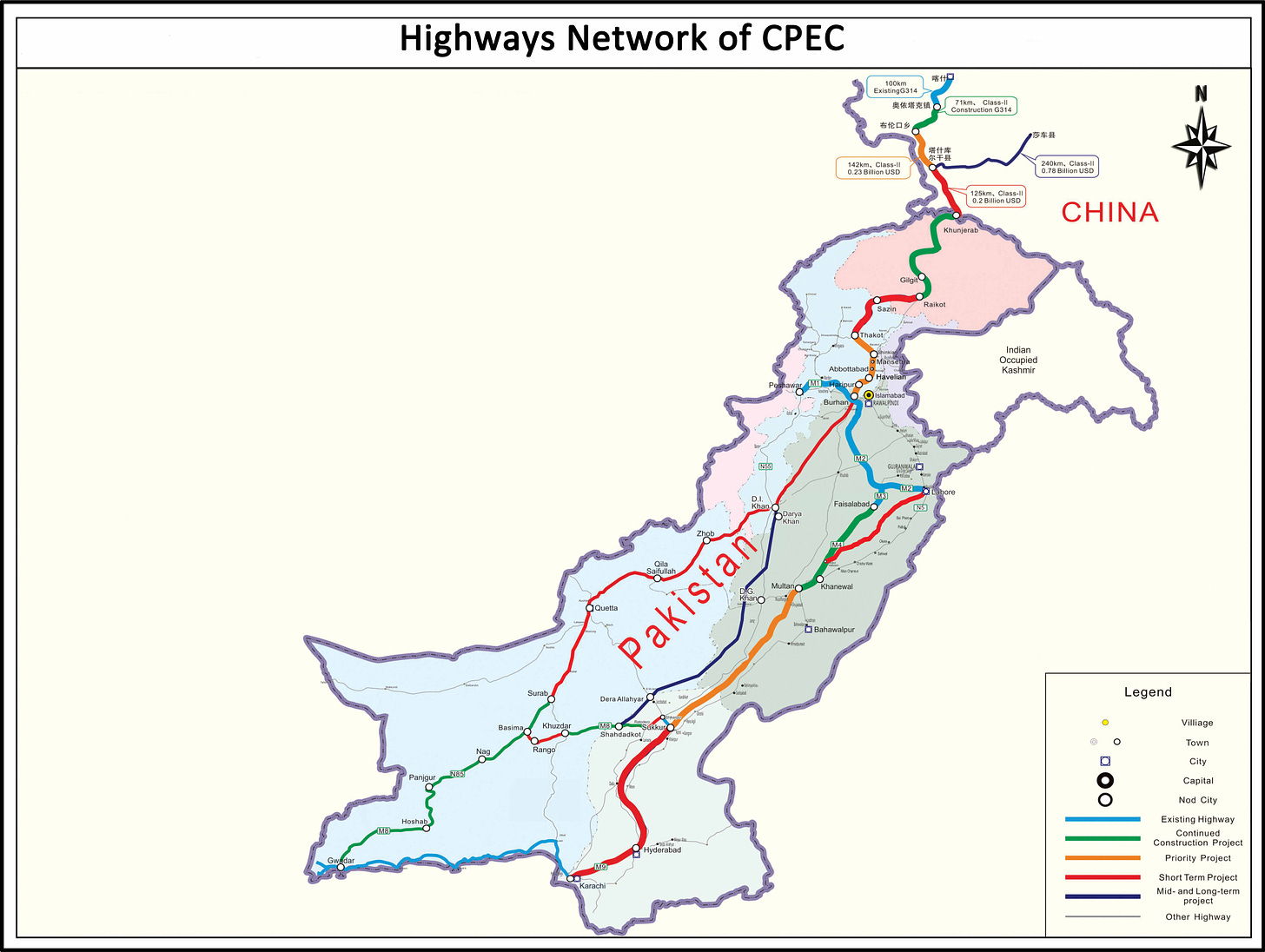

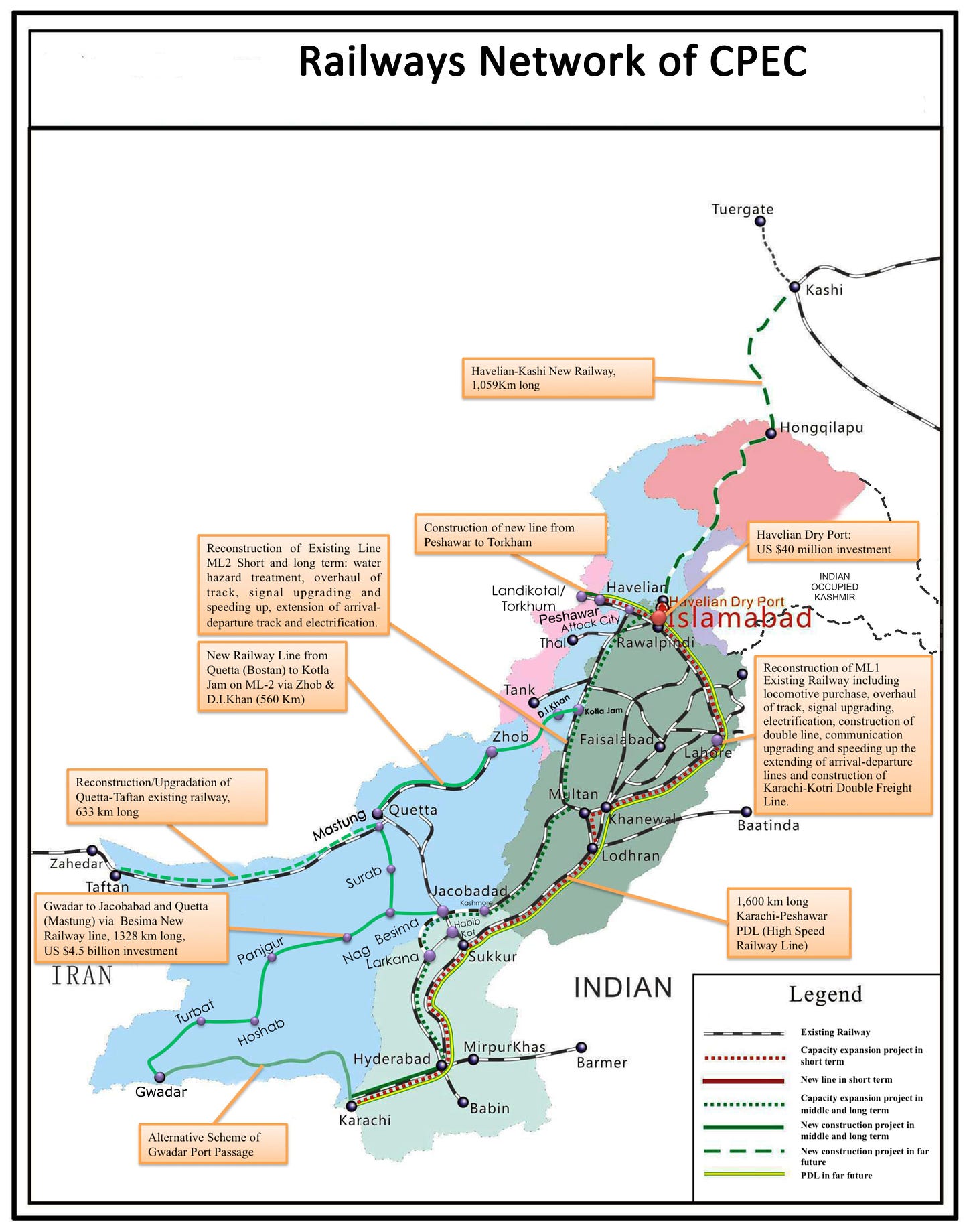

By extension it is also a major concern for China, which has seen a series of attacks on its citizens working on investments in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor this year. CPEC is a part of One Belt, One Road initiative and a strategically important series of infrastructural investments worth north of $60 billion, which are meant to provide Beijing with access to the Indian Ocean via port in Gwadar, circumventing choke-points in Southeast Asia and potentially hostile Indian waters.

Terror threats add to earlier disagreements and delays of CPEC projects over costs and timelines, souring bilateral relations and leading China to postpone the latest meeting scheduled for mid-July.

Afghanistan is also a concern for its possible influence in Xinjiang, where Beijing has long tried to suppress Uyghur separatism. Thousands of fighters who have thus far been occupied fighting the Afghan government, Americans and rival factions within Afghanistan, will now be left with little to do. Many of them may not be content serving under peacetime Taliban administration and can look for new military engagements across the country’s borders.

Just how wary China is of these developments was revealed by an unprecedentedly generous invitation to the Taliban for friendly talks to Tianjin in late July - weeks before the group actually took hold of the country.

Ironically, for all the troubles Taliban takeover in Kabul is causing its chief rivals in Islamabad and Beijing it spoils New Delhi’s plans too. Indian authorities have spent the past few years building friendly ties with the Afghan government to gain more leverage over Pakistan, hoping to encircle it from the west and north. They have also materially invested in an Iranian port and economic zone in Chabahar which was to provide a corridor into Central Asia, circumventing their hostile neighbor - both for economic and geopolitical reasons.

Even though the new Afghan government may, directly or not, cause problems for Islamabad, it’s unlikely that Indians are going to have any influence over it now.

Meanwhile, Iranian hosts of Indian ambitions in Chabahar stand to lose too - both on the unfinished and today quite questionable foreign investment, as well as the uncertainty over violence that may emerge from Afghanistan (particularly anti-Shiite sentiments and Taliban persecution of the mostly Shiite Hazara minority in the country in the past).

In fact, the conservative Iranian daily Kayhan, understood to be representing the views of the country’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, both downplayed the threat of the Taliban and accused the US of leaving Afghanistan to cause more problems for Iran - revealing a certain ambiguity and unease about the new administration in Kabul.

Post-Soviet republics of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and their patron, Russia, which has had its interest in the region for over 200 years, seem to be concerned as well.

Despite sending positive signals to the Taliban in recent days, Russia has also warned it that any incursions across the northern border (likely including violent groups which may use Afghanistan as their base of operations - like they have done in the past) would trigger a deadly response.

This suggests a good deal of uncertainty about the future of Afghanistan in Moscow.

Russia is obliged to intervene if any of the CSTO - Collective Security Treaty Organization - countries (grouping several former Soviet republics) is under attack. It reiterated this commitment by holding military drills with Uzbek (former-CSTO nation) and Tajikistan earlier in August.

Following the drills former Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces General of the Army Yuri Baluyevsky said in an interview with RIA Novosti that Russia could deploy long-range supersonic Tu-22M3 bombers (deployed for the drills from the base in Saratov) against the Taliban, should the situation require it.

Not something that you would call a “veiled” threat.

Laughter through tears

For all the mockery of American withdrawal coming from Moscow and Beijing, it really seems to be laughter through tears. Their actions reveal how wary they are of the change of guard in Kabul now that the US soldiers are done keeping the country relatively stable.

In comparison, America is risking very little leaving Afghanistan behind.

Even if gloomy scenarios were to materialize and major terrorist groups were to take root in the country they would hardly pose a threat greater than they already do, to anyone far from the country’s borders.

Not that they really need to (thanks to the internet), nor that the Taliban is likely to give them a free pass, since they are unlikely to risk wasting another 20 years just because another jihadist organization has drawn American backlash.

Despite the PR disaster that the way the withdrawal was conducted has caused, the burden of handling and stabilizing Afghanistan today falls on its neighbors and regional stakeholders - including those that Washington is not going to feel particularly sorry for.