Few things are more enjoyable than seeing evil autocrats – so long convinced of their invincibility – go out with a bang, especially with limited collateral damage to civilians.

Photos of handcuffed Nicolás Maduro, captured by US forces in a daring operation in Caracas last night, are going to forever enter the history books and should be welcomed by everybody who champions liberty.

But as impressive as this feat of American military is, this was really the easiest part of the entire operation. Somebody has to take charge of the country now – and run it well.

Even if we assume that Trump administration's success has made it clear to the regime's cronies that the USA will not accept any of them filling Maduro's position – and it's the democratic opposition, led by the latest Peace Nobel Winner, María Corina Machado, that is going to take over – it won't really solve Venezuela's problems, which have led the country to its current ruin.

And their source is and remains chavismo.

Venezuelan leaders may have been vilified in the developed world for the better part of the past three decades, but we have to accept that Maduro's charismatic predecessor, Hugo Chávez, had legitimately won four presidential elections on the trot, before cancer put an end to his life and political career in 2013.

For 15 years Venezuelans quite happily supported the fringe left-wing policies of chavismo and approved of its leader. Even if he occasionally exhibited some authoritarian tendencies, he was not an outright dictator and had always sought to ensure real support for his brand of populism.

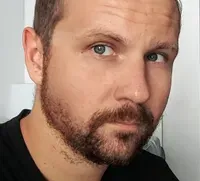

Despite numerous hardships, rampant crime and poverty, even in 2025 sources friendly to Venezuelan opposition placed approval for Maduro at 32% of the population, despite allegations of fraud during the 2024 election.

Yes, most people wanted him gone, but not as many as one would imagine. After all, Trump's approval among Americans is just over 43%. In Europe Maduro would outrank Macron, Starmer and Merz.

Westerners tend to assume that vocal opposition and public protests against leaders widely considered undemocratic surely mean the local population wants their country to be run like Europe or America.

In reality, however, they usually yearn for a slightly more palatable populist, especially given the often romanticised left-wing past of many Latin American societies, most of which have never shown any capability to learn from their very own history.

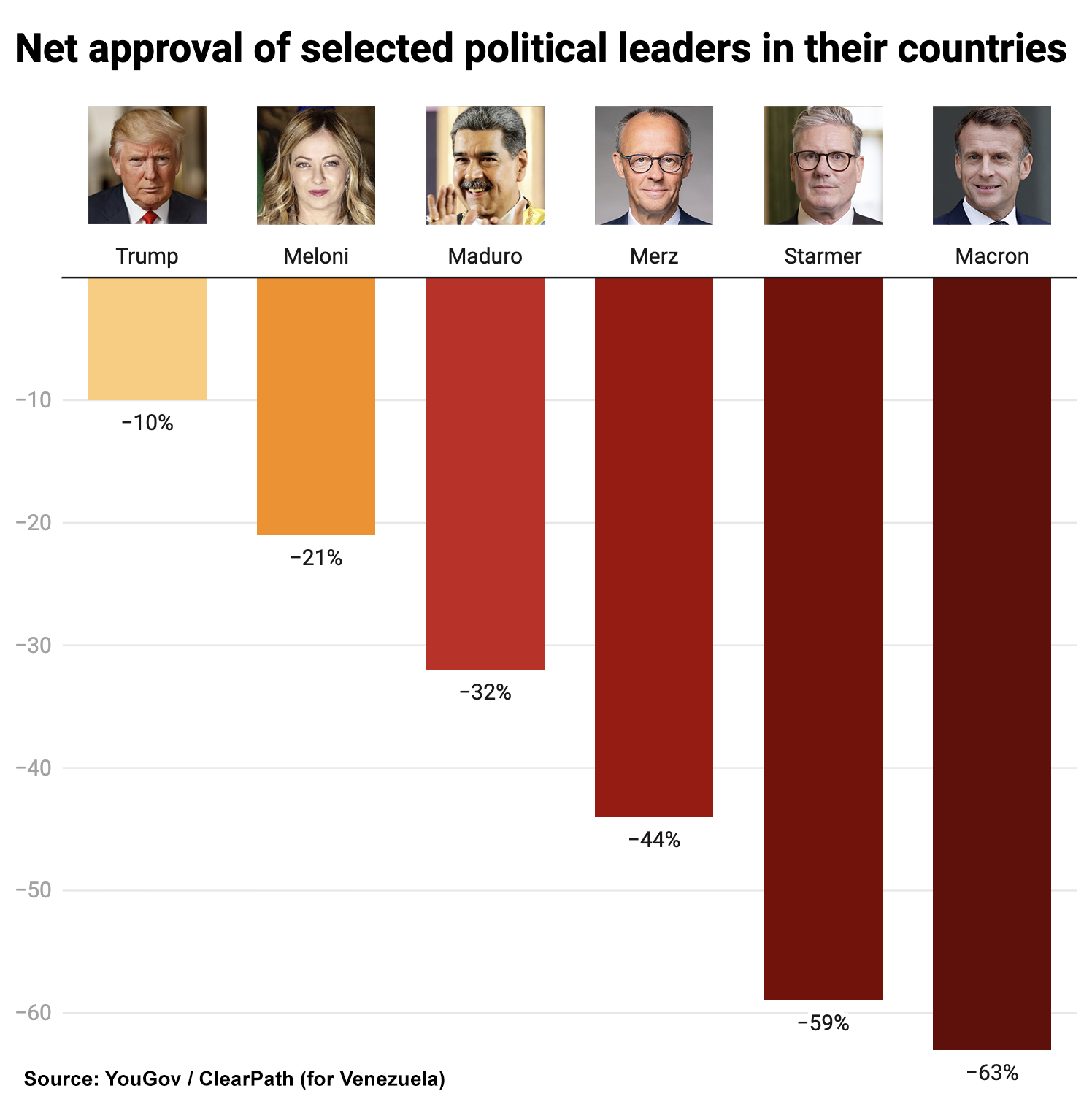

As recently as 2023 Associated Press reported that many Venezuelans missed Chávez, particularly as Maduro's ineptitude hit their living standards hard:

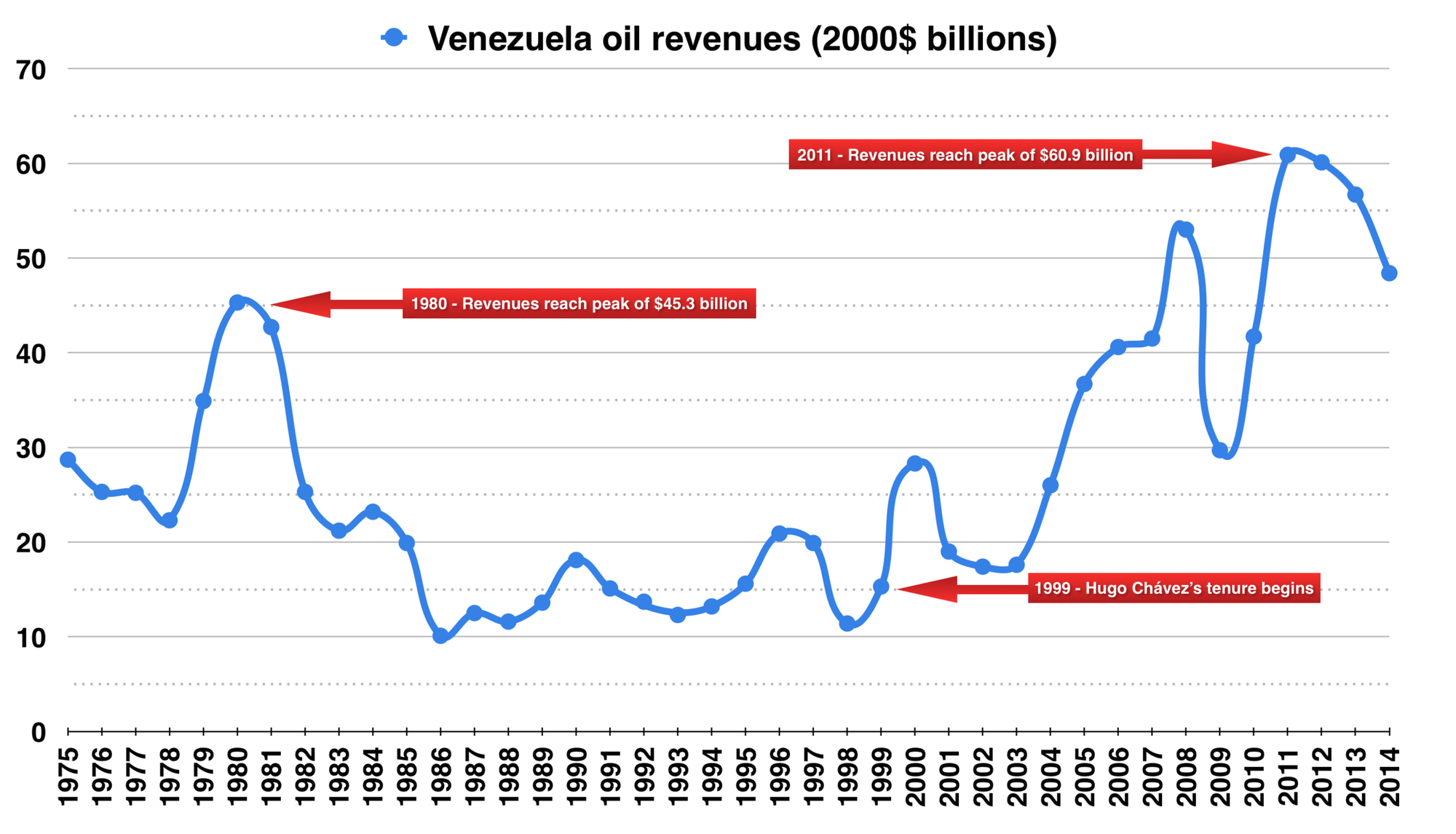

Most of them likely still do not understand just how badly their country was mismanaged during the oil boom from the early 2000s to mid-2010s, which enabled Chavez' generous tenure, during which he made the country almost entirely dependent on oil revenues and failed to prepare it for future crises.

What's more, the billions earned from selling crude softened somewhat the consequences of disastrous policies of widespread nationalisation, price controls or foreign-exchange controls imposed by the government, which had destroyed many companies, eroding non-oil industrial base while leading to crippling shortages of even most basic goods.

After oil prices had crashed in half by 2015 it became painfully clear that the country had nothing else to offer.

Maduro is blamed for everything today but in reality it was the bankruptcy of chavismo that brought Venezuela down. I'm not convinced that the public sees this.

What's more, domestic opposition is united in its desire to overthrow the regime and restore democracy in the country, but not in how the country should be run.

Machado might be drawing comparisons to Margaret Thatcher, but we would first have to see what the outcome of the next parliamentary election is, if and when it is held.

It's hard to expect that Venezuelans will suddenly turn out in their millions to support broad free market reforms, privatisation of state assets and dismantling of the, however illusory, state welfare system – a process which is guaranteed to bring even more pain before the situation can improve.

The elephant in the room

Finally, there's the question of whether the new government can exercise authority over the armed forces and the police, which Maduro has turned into accomplices in pillaging whatever was left in the country.

Rewarded with money and lucrative positions in state enterprises, are the current and former officers going to obey the new leaders, whom they were once deployed against? What about the legal accountability for the crimes of the regime?

Are the men with guns going to quietly take the risk of lengthy prison sentences? Should they be granted amnesty? And even if so, their comfortable lives are bound to soon be over anyway. Won't they resist?

Perhaps the long shadow cast by the US president and the display of American military might in Caracas may temper the revolutionary moods in the ranks – but Trump is going to remain in the White House for just three more years. Can Machado and her allies assume enough control in this time to prevent a future blowback from those they are planning to get rid of today? Can they rein in corruption and combat drug smuggling? Finally, can they get the society on side and prevent rise of yet another populist, who could ride to electoral victory on widespread sentiment for Hugo Chávez one day?

Looking at the history of other countries in South America it's hard to be optimistic.