As Trump is heading to meet Putin today, we shouldn't expect a major breakthrough, although a temporary, symbolic ceasefire is possible. Russians are going to try to feel Trump out and appease him for as long as it works in staving off additional sanctions or military aid to Ukraine.

Earlier this year Trump resorted to mobster methods of extortion to force Volodymyr Zelensky to talk peace with Russia, making it seem that the war may find its conclusion in less than another 3 years that have elapsed since the invasion.

However, with Russians stalling for as long as they have even the tiniest battlefield advantage, it doesn't seem that it's going to happen as quickly as Trump envisioned – unless he is really ready to increase the pressure.

Whatever happens Ukraine cannot hope to regain control over any territory that it has lost since 2014. Russians won't agree to it and Trump won't force them to either.

However, that wouldn't necessarily be bad for the tormented country.

While Ukrainian president has always resisted the idea of ceding anything to Russia, the reality – surely understood in Kyiv as well – is that not only it is going to have to compromise but such an ending would actually be with benefit to its future – under certain conditions.

Divided at birth

Ever since it emerged out of USSR in 1991, Ukraine has had the misfortune of being a highly polarised society.

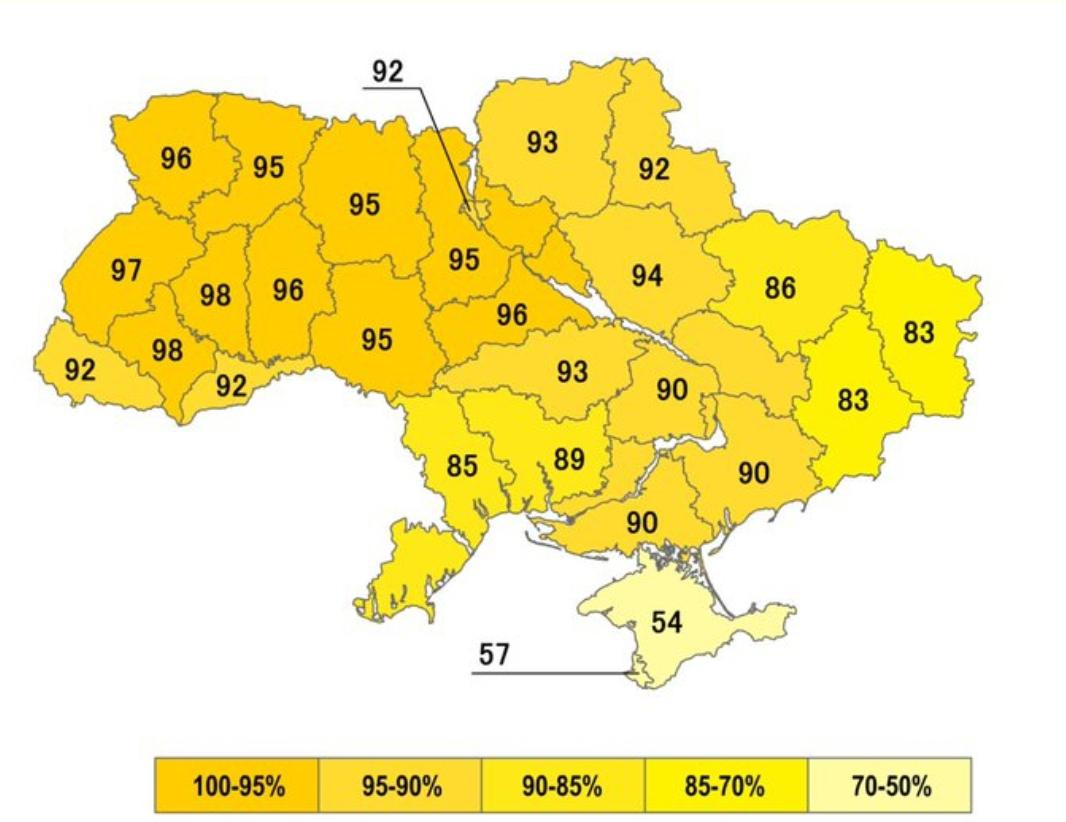

Even though a vast majority of its citizens voted in favour of independence – including in Crimea – in the referendum of 1991, the reality has long been that the east and the west of the country had different ideas about their shared future.

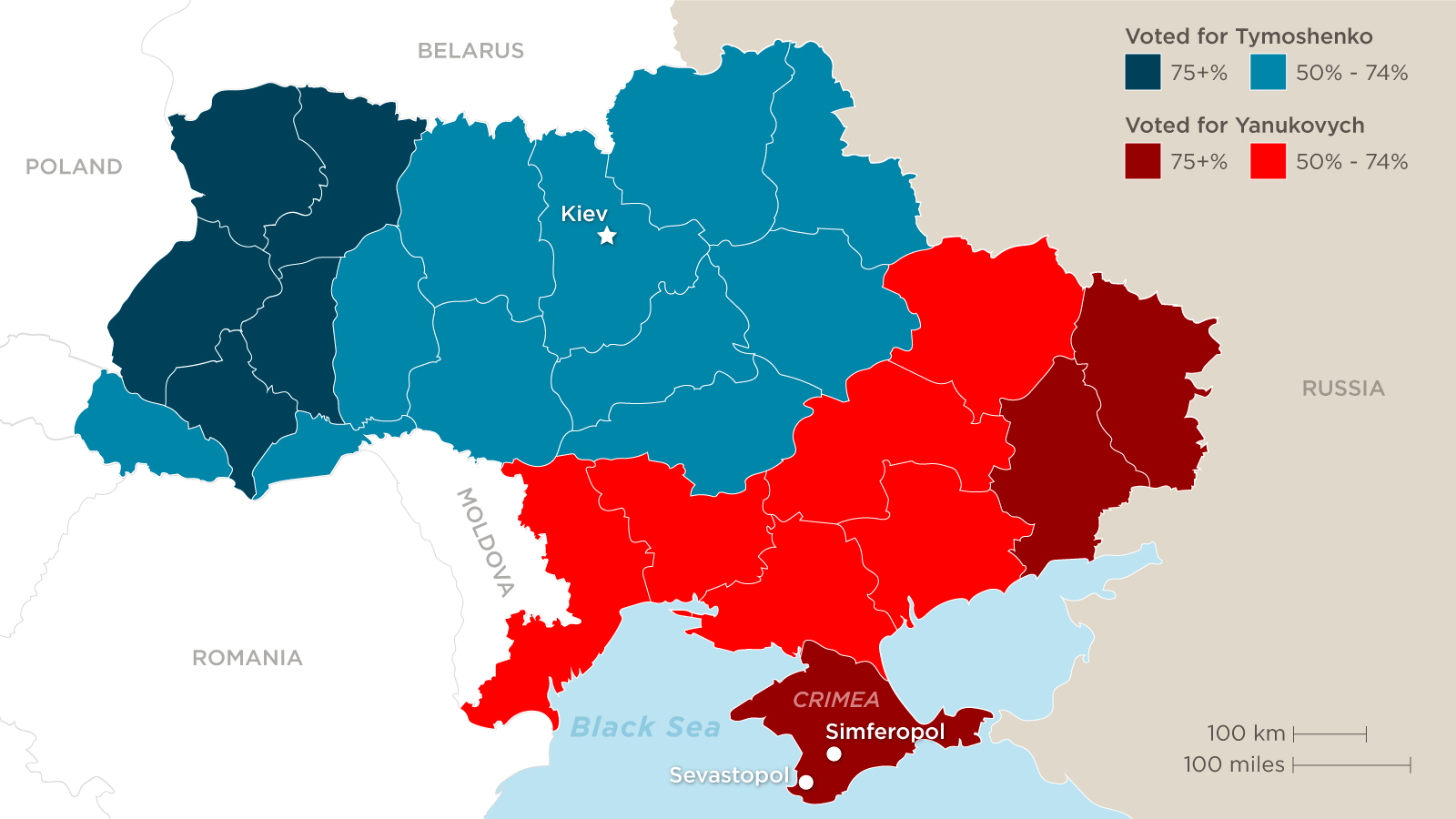

This has translated into repeated political instability and controversies which followed the last few presidential elections, with swings between the pro-European and pro-Russian camps over the years.

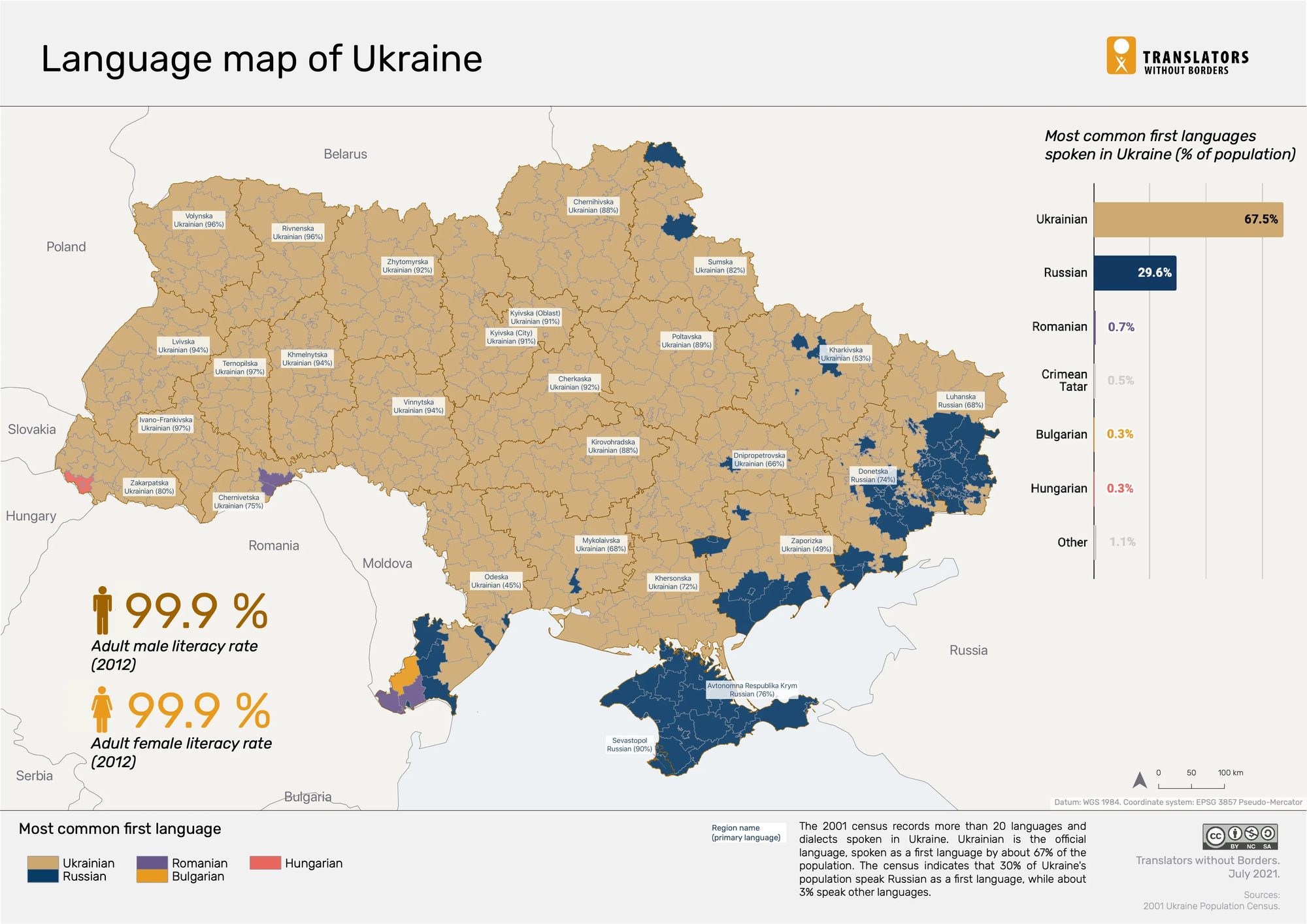

With both a higher concentration of native Russians and Russian speakers in the east, as well as their physical proximity to Russia itself, cracks were bound to happen eventually – especially given Kremlin's history of meddling in neighbouring countries to maintain a sphere of influence and kleptocratic relations filling the pockets of corrupt oligarchs on both sides.

Should Ukraine miraculously retain those regions, the same problems would re-emerge with time, as it would be hard to imagine forced resettlement of all Russians and repopulation with native Ukrainians (whose numbers are dwindling anyway).

Many enemies of independent Ukraine would continue to have a vote about its future, eventually dragging it back towards Russia, just like Yanukovych did.

Jettisoning them off would help cement the pro-European direction, reducing its opponents to a permanently small minority in the society.

Sure, Ukraine would lose access to the mineral wealth of oil, gas and coal, but there are more countries which are successful without than thanks to them. The resource curse is very real.

There's hardly any reason for Ukraine to hold onto the territories that have caused it so much trouble for so long, even before the war. After decades of stagnation compared to its former Eastern Bloc EU neighbours like Poland, Slovakia or Hungary, it could be the change the country needs to finally jump forward.

However, giving up the east would also set a very dangerous precedent that triggers nightmares in the rest of Europe (and the world).

Slippery slope

When Russia seized Crimea in 2014 the EU was understandably upset and imposed some sanctions on Russia, but deep inside everybody felt that given the bloodless takeover there and large Russian population on the peninsula and in the far east oblasts of Luhansk and Donetsk, they could live with the status quo.

Hot war was limited to relatively small areas 1000km away from the nearest EU border, while Kremlin's propaganda wasn't entirely baseless given the share of native Russians living there.

That was enough of an excuse to allow the limp-wristed European bureaucrats to live with that reality, explaining it to themselves as the usual mess in the post-Soviet world.

However, when rockets began raining down on Kyiv or Lviv, close to the Polish border, and Russian forces began indiscriminate bombings of civilian infrastructure, with an obvious goal of annexation of the whole country, Europe realised it has to face the first major war on its doorstep since WW2.

And it is a war against the EU, not Ukraine alone.

Implosion of Yugoslavia and resulting fighting in the Balkan melting pot in the 1990s were essentially a regional conflict that did not pose a direct threat to the continental order. New countries emerged eventually and have maintained peace for a quarter of a century, all lining up for a future membership in the European Union.

Russian partitioning of Ukraine, however, is about to legitimise forceful boundary changes in the 21st century Europe – something that the West thought was relegated to history books.

European leaders simply cannot accept it, because it would undermine the entire post-WW2 security order that has kept the continent intact for 80 years.

If Russians can wage war on Ukraine – and no longer merely under the guise of protecting their own minority there, but questioning the entire country's existence – they could soon do the same to Belarus or the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, members of both the EU and NATO.

If European capitals rubber-stamp Putin's annexation of Ukrainian east, they would be paving the way to further claims against the countries on the union's and NATO's eastern flank, as well as Finland, Norway and disputed areas in the Arctic.

Estonia and Latvia have sizeable Russian minorities of around 25% each. And while it's just 5% in Lithuania, that country of less than 3 million people is what Moscow needs to link its isolated Kaliningrad oblast to the rest of the motherland via Belarus (which is likely to be formally annexed at some point) – closing the Suwałki Gap.

It is a goal similar to that which Hitler stated, demanding an extraterritorial corridor to the free city of Gdansk (Danzig) and the German East Prussia from Poland in 1938 – with the Polish refusal being the justification for the subsequent Nazi invasion that started the World War 2.

Recognising Russian possessions in Ukraine will also encourage destabilisation in other regions around the world.

After all, if one of the major global powers can shift borders around with brute force, while the entire civilised West eventually folds to its will, why shouldn't other countries do it to their neighbours?

It would be doubly hypocritical of European leaders, considering their recent pressure on Israel over its war in Gaza – which is waged in self-defence, following Hamas' attack in 2023.

Why should Israel back down if Europeans accept Russian annexation of parts of Ukraine? Why should it not claim parts of Gaza or the entire West Bank? Especially if it is the one being constantly attacked?

If the Russian conquest is accepted by Europe and America, even if not formally recognised, the entire civilised global order will fall apart as a result. It becomes a free for all where might makes right.

Paradoxically, besides Russia Ukraine would be the one that benefits the most if that happened. For the rest of us it's a precedent that would pave the way to far more bloodshed around the world.