Days go by and protests in Hong Kong appear to increase in severity and irrationality, instead of dying down. I have explained here why they are quite senseless and will only result in more harm for the wealthy city.

However, in the ensuing propaganda war, a lot of misleading information has been circulated about both sides - with the most egregious and ignorant one pointing out that United Kingdom, the colonial custodian of the city, never gave its people democracy either. So why, the critics say, should they expect it from China?

Now, hysterical youth in Hong Kong may be blind and reckless but the reason their city was never granted more rights is the same as the reason for their protests today.

Democracy? What's that?

Britain is often considered the cradle of modern democracy, with progressively greater liberties granted to the people over the 800 years following the Magna Carta. In reality, however, it wasn't until 1918 when all males were finally granted suffrage and 1928 when all women were included as well.

Therefore, as I write these words, democracy as we've come to understand it is less than a century old - even in the UK itself.

Understandably, it would have been hard to expect to see it granted to or developed in distant colonies earlier than that. As a result, it wasn't until the end of World War 2 when the concept of independent nation states, governed by the will of their people, built out of existing European colonies, began to accelerate.

The good guy Young

The first time popular elections were considered as a means of empowering Hongkongers to participate in governance was in 1946, suggested by then governor Mark Young, who sought to establish a distinct identity among the locals and give them a stake in the decision making processes, to counter influence of the mainland China and its leadership.

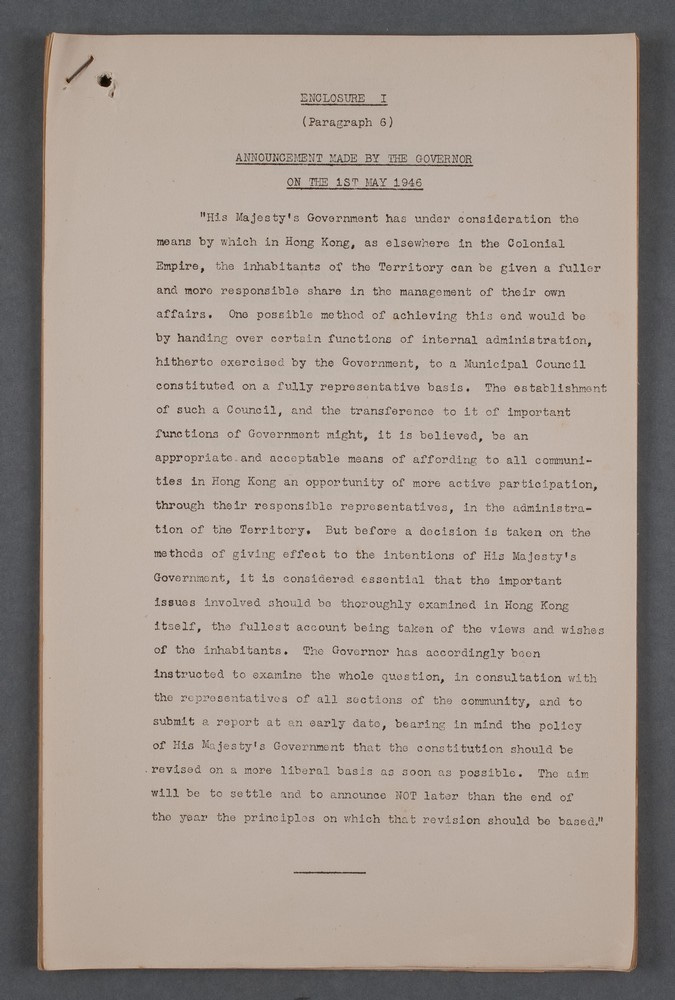

In May 1946, after gaining approval from London, he made the following announcement:

"His Majesty's Government has under consideration the means by which in Hong Kong, as elsewhere in the Colonial Empire, the inhabitants of the Territory can be given a fuller and more responsible share in the management of their own affairs. One possible method of achieving this end would be by handing over certain functions of internal administration, hitherto exercised by the Government, to a Municipal Council constituted on a fully representative basis." / Mark Young

You can view it in full below:

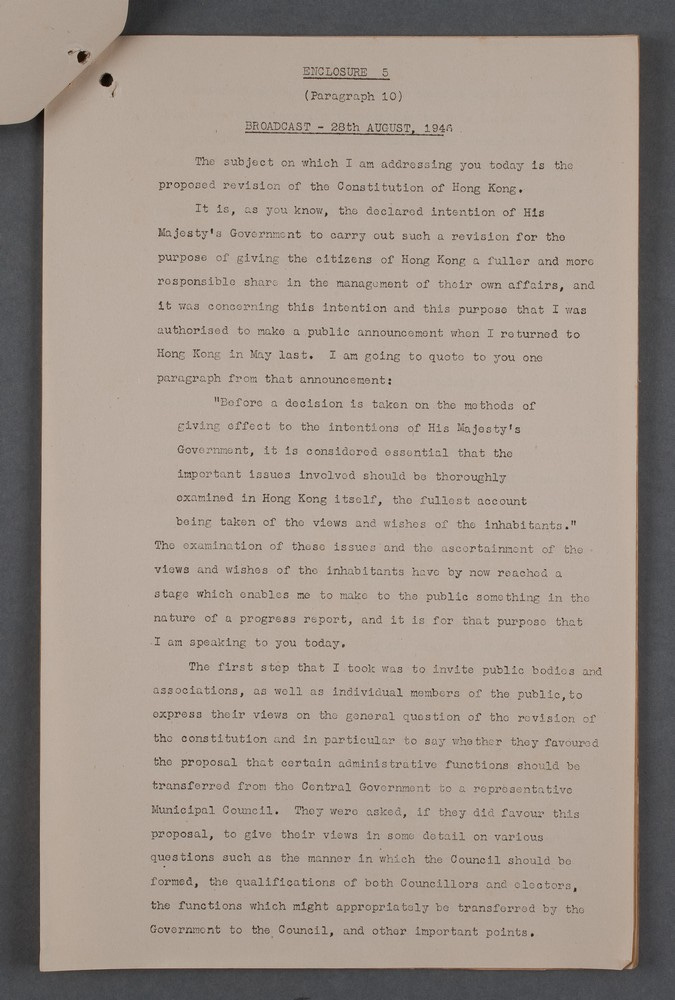

After engaging the public and collecting feedback on the proposed changes, the governor issued the follow up in September 1946:

"The subject on which I am addressing you today is the proposed revision of the Constitution of Hong Kong. It is, as you know, the declared intention of His Majesty's Government to carry out such a revision for the purpose of giving the citizens of Hong Kong a fuller and more responsible share in the management of their own affairs..." / Mark Young

British government was receptive to Young's ideas but, unfortunately, the same couldn't have been said about his successor, Alexander Grantham who took over in 1947 when Young was struggling with health issues.

Long story short, the proposal faced opposition and in the face of Maoist victory in 1949 and establishment of People's Republic of China, democratisation Hong Kong was shelved, given the spread of communism in the early years of Cold War.

Especially as the conflict wasn't exactly so 'cold' across Asia - wars ravaged Vietnam and broader Indochina since 1945 until 1989 (on multiple fronts and with multiple participants), Korean war erupted in 1950 (with ample Chinese support for Kim Il-sung) and, in the south, Malaysia - still under British control - struggled with its own communist insurgency as well.

The topic of liberalization of Hong Kong's politics has continued to re-emerge at various points throughout the 50s and the 60s, but by then the opposition to it was no longer internal.

China

After Maoist victory in 1949, China began reasserting itself on the global stage - whether it liked it or not (e.g. like it was maneuvered by Stalin into intervening in the Korean War). It was clear that despite decades of Civil War and the World War suffering under Japanese occupation, it was a formidable power - and a one capable of both military action as well as defiance of anything that the West can throw at it, including nuclear weapons, as stated by Mao himself in 1957:

“I’m not afraid of nuclear war. There are 2.7 billion people in the world; it doesn’t matter if some are killed. China has a population of 600 million; even if half of them are killed, there are still 300 million people left.” / Mao Zedong

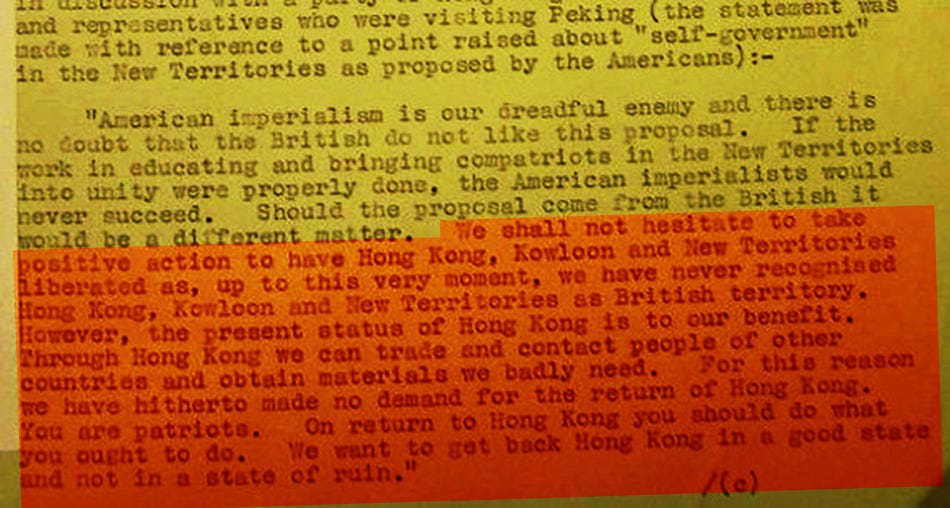

This spirit was evident also during a meeting with the British in 1958, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai made it quite clear that PRC would not accept any attempts at democratisation of Hong Kong and threatened to use force should such a thing ever happen:

In the meanwhile the country was busy developing its own atomic bomb - an endeavor concluded with a successful test in 1964.

Given the geopolitical situation of the time - prolonged wars, American ultimate defeat in Vietnam, and Chinese support for communist regimes in the region, coupled with repeated threats of intervention made by Beijing, addressing the contentious matter of Hong Kong had to wait - for another 20 years.

With the opening of China to the world (thanks to Deng Xiaoping) and approaching expiration of the lease of Hong Kong to Britain, talks over the future of the territory began in the late 1970s, leading to the Joint Sino-British Declaration in 1984 that stipulated the future of Hong Kong.

In the memoirs published in 1993, Margaret Thatcher revealed the tone of discussion about political reforms in the city - with unwavering Chinese rejection of any attempts at installing democracy and a threat, made by Deng himself, that China could seize Hong Kong in a day if it wanted to.

Ever since the 1950s it was clear that PRC kept its eyes on the prize (regardless of who was in charge), waiting the situation out until 1997, when United Kingdom would cease to have legal grounds to keep hold of Hong Kong.

Allowing any democratic processes to take root there would be a clear first step to self-determination, which could end with a declaration of independence of the city - and it is not something Beijing could accept without a fight (much like the independence of Taiwan).

The window in which the British could have introduced democracy in Hong Kong was very narrow - from the end of the World War 2 to the establishment of People's Republic of China, when governance in Beijing was still in disarray. Outside of that 3-4 year period it was either too early or far too late to do it. Pressure from an assertive, nuclear-armed state which repeatedly warned of military action should people of Hong Kong be given the right to vote, was not something London could respond to.

Paradoxically, then, it served Beijing's interests to have colonial administration in place until the handover could commence, rather than allow the local Chinese to decide what they want for themselves.

Given its weakening position and vicious global conflicts of the time, Britain was not in a position to challenge China, likely hoping - at least in later years - that increasingly more open PRC would eventually become more civilized and democratic itself.

This dream - widely indulged in the West for decades - proved to be a mirage. Of course British motivations for reforming Hong Kong's governance were hardly idealistic - ultimately, they were meant to serve its political interests.

That said, crude accusations that the UK somehow denied the people of Hong Kong the right to participate in governance are a blatant manipulation conveniently omitting the crucial fact that London was forced to abandon its numerous plans to do so due to persistent threat of use of force by Beijing.

The very same threat which, today, pushes thousands of Hongkongers to take to the streets and protest (regardless of how (un)reasonable it is).

While I don't think anybody can demand China to govern itself in any way other than it wants to, I do believe that we can at least expect the rising superpower (which has certain global responsibilities) and its acolytes, to - at the very least - accept simple historical facts.